The Cultural Revolution

Introduction

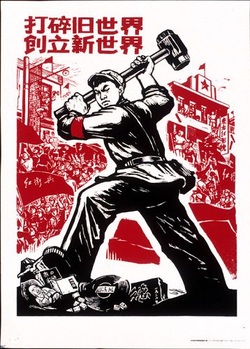

The propaganda poster pictured on the left is a perfect starting point for a discussion of the cultural revolution that occurred in China between 1966 and 1976. The Chinese writing at the top of the poster says, "Destroy the old world, rebuild a new world." Underneath the worker's foot is a representation of music, literature, religious symbols, and items that would oppose the creation of Mao Zedong's new China. This was the mentality instilled in young Chinese minds during this 10-year revolution. Chairman Mao sought to remove all traces of capitalism in order to further advance the Chinese socialist system. This meant the destruction of anything that would remind the Chinese people of their past in order to remove all distractions from the creation of a new China. The chaos that this movement created slowly disintegrated every level of social and political structure in China. The aftermath is still visible today and the majority of Chinese people prefer not to discuss this traumatic period of their history.

The Cultural Revolution is a very complicated topic to dissect. The length of the revolution combined with its deep connection to almost every facet of Chinese society makes it almost impossible to briefly summarize. For the purpose of my research, I have chosen to focus on the end of the revolution and its effects on the arts. The understanding of this difficult period of Chinese history gives excellent insight as to how and why China developed into the country it is today.

The Cultural Revolution is a very complicated topic to dissect. The length of the revolution combined with its deep connection to almost every facet of Chinese society makes it almost impossible to briefly summarize. For the purpose of my research, I have chosen to focus on the end of the revolution and its effects on the arts. The understanding of this difficult period of Chinese history gives excellent insight as to how and why China developed into the country it is today.

The Beginnings of a Revolution

Those representatives of the bourgeoise who have snuck into the Party, the government, the army, and various spheres of culture are a bunch of counter-revolutionary revisionists. Once conditions are ripe, they will seize political power and turn the dictatorship of the proletariat into a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. Some of them we have already seen through; others we have not.

-May 16th Notification, 1966

The text above is a segment from Zhongfa 267, a collection of documents dubbed the "May 16th Notification" which discussed the dismissal of several high ranking members of the communist party during 1966. The dismissal was prompted by certain members of the Communist Party trying to prevent Maoists from having unrestricted access and control of the press. This particular section was written under the strict supervision of Chairman Mao and was the first written document that indicated that the "Great Cultural Revolution" had begun. Although written in 1966, this document along with many others were kept top secret until May of 1967 in order to prevent interference from dissenting parties until the Communist Party was ready to act. This section of the Zhongfa 267 document expresses the core of Mao's political ideology. Mao believed that the bourgeoise (social class of capitalists) had been in control of China for far too long. He sought to strip them of their power and give it to the rightful owners; the proletariat (industrial working class). This idea of a "dictatorship of the proletariat" originally comes from the teachings of Marxism, a socio-political view that Mao greatly admired. The basic concept of a "dictatorship of the proletariat" is that the working class is in control of the government and thus removes any chance of being exploited by capitalists. Considering the massive size of the working class in China, it is easy to see why this idea was so appealing to Chinese citizens.

Even before the Zhongfa 267 document was published, Mao's vision for the working class was well known by the Chinese people. The idea that the Chinese people could potentially have the power to control the government was a very popular notion. Especially considering that only five years earlier China experienced one of its worst famines in history. Known as the "Three Bitter Years," the Chinese government estimates that around 15 million people prematurely died between 1958 and 1961. The famine was caused by a combination of extremely poor weather conditions and the failure of the "Great Leap Forward" (a government plan which tried to rapidly move China from an agrarian country to an industrial country). The reduced number of farms from the industrial reorganization mixed with the drought and bad weather was devastating to the food supply. Many modern day researchers estimate that the actual number of premature deaths was much closer to 40 million than 15 million. Wanting their country to never experience such a traumatic event again, many Chinese showed great support for Mao and his plan for the people. In particular, Chinese scholars showed a strong desire to become leaders within their communities in order to promote the Communist Party. The most notable example of this kind of leadership occurred in Beijing in May of 1966. A young lecturer from Peking University named Nie Yuanzi accused the university and local government of trying to betray and impede the progress of Mao's revolution through the teaching of elitist and bourgeoisie ideas. The protest quickly gained local support as well as Mao's attention. Within a few short days, Chairman Mao had Yuanzi's message nationally broadcast as a call to neutralize and punish all those who opposed the progress of Mao's revolution. Mao's support of Nie Yuanzi prompted numerous students and young people to come forward and band together to ensure the success of the Cultural Revolution. This was the birth of the Red Guard.

Even before the Zhongfa 267 document was published, Mao's vision for the working class was well known by the Chinese people. The idea that the Chinese people could potentially have the power to control the government was a very popular notion. Especially considering that only five years earlier China experienced one of its worst famines in history. Known as the "Three Bitter Years," the Chinese government estimates that around 15 million people prematurely died between 1958 and 1961. The famine was caused by a combination of extremely poor weather conditions and the failure of the "Great Leap Forward" (a government plan which tried to rapidly move China from an agrarian country to an industrial country). The reduced number of farms from the industrial reorganization mixed with the drought and bad weather was devastating to the food supply. Many modern day researchers estimate that the actual number of premature deaths was much closer to 40 million than 15 million. Wanting their country to never experience such a traumatic event again, many Chinese showed great support for Mao and his plan for the people. In particular, Chinese scholars showed a strong desire to become leaders within their communities in order to promote the Communist Party. The most notable example of this kind of leadership occurred in Beijing in May of 1966. A young lecturer from Peking University named Nie Yuanzi accused the university and local government of trying to betray and impede the progress of Mao's revolution through the teaching of elitist and bourgeoisie ideas. The protest quickly gained local support as well as Mao's attention. Within a few short days, Chairman Mao had Yuanzi's message nationally broadcast as a call to neutralize and punish all those who opposed the progress of Mao's revolution. Mao's support of Nie Yuanzi prompted numerous students and young people to come forward and band together to ensure the success of the Cultural Revolution. This was the birth of the Red Guard.

The Red Guard

The first group of students to identify themselves as members of the "Red Guard" were from Tsinghua University Middle School in late May of 1966. Although called a middle school, Tsinghua University Middle School was actually a high school attached to Peking University and was revered as one of the best high schools in China (it is still considered to be the one of the most prestigious high school to this day). These students felt that Yuanzi's criticisms of the Peking University were serious political issues and were not being taken seriously enough by the government. The creation of the Red Guard was their way of expressing the importance of this issue as well as a way to contribute to the revolution. The Red Guard began its career by assisting Nie Yuanzi in her protesting and inducted her as a member. Shortly after Yuanzi gained support from Mao and the Communist Party, so did the Red Guard. Mao ordered the manifesto of the Red Guard to be published in the national newspaper, legitimizing the group and their cause. It was not long before the youth of China began to embrace the Red Guard and form chapters all around China.

As the number of Red Guard members rapidly increased, the original purpose of the group started to lose focus. The group of students who originally formed the Red Guard wanted to remove capitalist teachings from the universities and discourage intellectual elitism. However, each new chapter of the Red Guard that emerged around China adapted the original Red Guard's manifesto to combat each individual chapter's local social and political issues. This lack of organization concerned the Communist Party, prompting the creation of "work teams" in early June of 1966. These teams, headed by the Party's department of propaganda, were sent to every major chapter of the Red Guard to ensure that the Red Guard was always operating in the best interest of the Communist Party. The Party's main goal with these work teams was to divert any attacks or criticisms on government officials to "bourgeois" elements present in Chinese society. In this effort to redirect criticism, the finger was often pointed at intellectuals. This sparked a wave of dissatisfaction with the curriculum being taught in China's education system.

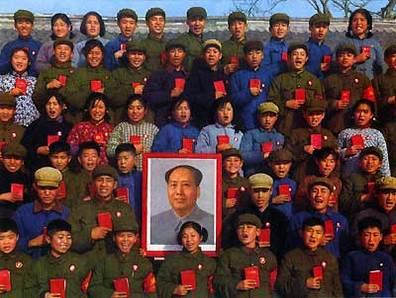

Only 50 days after beginning the Party's "work teams" program, Chairman Mao ordered the dissolving of the program along with the removal of all work team members from the Red Guard. Many of Mao's advisors disagreed with this decision, but Mao felt that the work teams were hindering the progress of the Cultural Revolution. He even went so far as to publicly condemn the period of time the teams were integrated into the Red Guard, calling it the "fifty days of white terror." The lack of Party presence in the Red Guard allowed the Guard to operate anyway it saw fit. This new privilege of power given to the Red Guard combined with Mao's support, fueled Chinese youth's desire to join the cause. Within a few short weeks, a chapter of the Red Guard could be found in almost every school in China. Armed with Mao's little red book of quotations and political speeches, the youth of China prepared itself for its roll in the Cultural Revolution.

As the number of Red Guard members rapidly increased, the original purpose of the group started to lose focus. The group of students who originally formed the Red Guard wanted to remove capitalist teachings from the universities and discourage intellectual elitism. However, each new chapter of the Red Guard that emerged around China adapted the original Red Guard's manifesto to combat each individual chapter's local social and political issues. This lack of organization concerned the Communist Party, prompting the creation of "work teams" in early June of 1966. These teams, headed by the Party's department of propaganda, were sent to every major chapter of the Red Guard to ensure that the Red Guard was always operating in the best interest of the Communist Party. The Party's main goal with these work teams was to divert any attacks or criticisms on government officials to "bourgeois" elements present in Chinese society. In this effort to redirect criticism, the finger was often pointed at intellectuals. This sparked a wave of dissatisfaction with the curriculum being taught in China's education system.

Only 50 days after beginning the Party's "work teams" program, Chairman Mao ordered the dissolving of the program along with the removal of all work team members from the Red Guard. Many of Mao's advisors disagreed with this decision, but Mao felt that the work teams were hindering the progress of the Cultural Revolution. He even went so far as to publicly condemn the period of time the teams were integrated into the Red Guard, calling it the "fifty days of white terror." The lack of Party presence in the Red Guard allowed the Guard to operate anyway it saw fit. This new privilege of power given to the Red Guard combined with Mao's support, fueled Chinese youth's desire to join the cause. Within a few short weeks, a chapter of the Red Guard could be found in almost every school in China. Armed with Mao's little red book of quotations and political speeches, the youth of China prepared itself for its roll in the Cultural Revolution.

The Four Olds

The formation of the Red Guard gave Chairman Mao a seemingly unstoppable army comprised of China's youth. Members of the Red Guard pledged their undying loyalty to Mao and hung on his every word. This devotion was so passionate that it caused fragmentation within the Red Guard based on interpretations of the often vague speeches Mao gave. Certain factions would even get into verbal and physical fights over who was interpreting Mao's will correctly and serving him the best. Mao witnessed this incredible devotion from the Red Guard and knew that the Cultural Revolution was now in full swing. All that was missing was a clear mission for the Red Guard to carry out.

On August 18th 1966, Chairman Mao held a rally in Tiananmen Square for the Red Guard. It is estimated that there were over ten million members of the Red Guard present. Wearing a red arm band to show his support of the Guard, Mao gave one of the most influential speeches of his political career. In this address, he discussed the newly ratified Sixteen Points. This was a document that laid out the goals of the Cultural Revolution and the means by which to accomplish them. In addition to explaining the content of the Sixteen Points document, he clearly laid out the role that the Red Guard was to play in the Cultural Revolution. The central goal that Mao wanted the Guard to accomplish was the destruction of the "four olds" of Chinese society: old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas. This marked the beginning of one of the darkest times in Chinese history.

As the message spread throughout the Red Guard, so began the destruction of the four olds. Museums were ransacked, books were burned, shrines and idols desecrated, and anything else that had any shred of connection to the "old" China was underly destroyed. If something was too big to tear down, it was often covered in red paint and adorned with quotes from Mao's little red book. Music was also a target of this revolutionary purge. Everything from recordings to traditional instruments were destroyed in order to pave the way for China's new music. Some Red Guard members took this purging of the four olds so far, they referred to the destruction of China's old religious relics as "the death of God." At first, the war path of the Red Guard only targeted relics and objects that represented of the old ways of China. However, it was not long before the Red Guard aimed their sights on what they believed to be the true source of the four olds plaguing China; the Chinese people.

On August 18th 1966, Chairman Mao held a rally in Tiananmen Square for the Red Guard. It is estimated that there were over ten million members of the Red Guard present. Wearing a red arm band to show his support of the Guard, Mao gave one of the most influential speeches of his political career. In this address, he discussed the newly ratified Sixteen Points. This was a document that laid out the goals of the Cultural Revolution and the means by which to accomplish them. In addition to explaining the content of the Sixteen Points document, he clearly laid out the role that the Red Guard was to play in the Cultural Revolution. The central goal that Mao wanted the Guard to accomplish was the destruction of the "four olds" of Chinese society: old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas. This marked the beginning of one of the darkest times in Chinese history.

As the message spread throughout the Red Guard, so began the destruction of the four olds. Museums were ransacked, books were burned, shrines and idols desecrated, and anything else that had any shred of connection to the "old" China was underly destroyed. If something was too big to tear down, it was often covered in red paint and adorned with quotes from Mao's little red book. Music was also a target of this revolutionary purge. Everything from recordings to traditional instruments were destroyed in order to pave the way for China's new music. Some Red Guard members took this purging of the four olds so far, they referred to the destruction of China's old religious relics as "the death of God." At first, the war path of the Red Guard only targeted relics and objects that represented of the old ways of China. However, it was not long before the Red Guard aimed their sights on what they believed to be the true source of the four olds plaguing China; the Chinese people.

From Revolution to Rampage

Mentioned earlier, the Communist Party sent workers to assist the newly formed Red Guard in an attempt to deter the Guard from criticizing government officials. In their effort to pull the government out of the spotlight, they inadvertently put intellectuals and the education system in the line of fire. As the destruction of the four olds unfolded, the Red Guard met resistance from many scholars and intellectuals. Believing that there was no place in Mao's new China for capitalists or proponents of elitist thinking, the Red Guard began to take a much more violent approach to their eradication or the four olds.

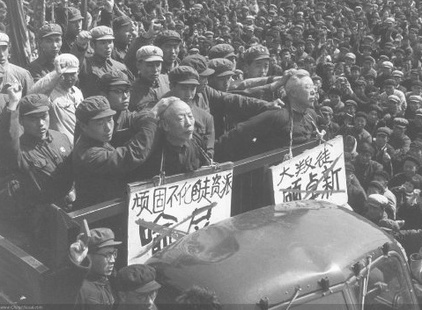

In the Sixteen Points document, its is clearly stated that persuasion rather than violence should be utilized in the realization of the Cultural revolution. However, the Red Guard ignored these guidelines. The Guard was more concerned with the absolute success of the Revolution by any means necessary. The persecution of intellectuals began with the Guard shutting down educational institutions and forcing the staff to do manual labor all day in order to give them time to "reflect on their mistakes." In the eyes of the Red Guard, the intellectual class being persecuted was not limited to members of the academic community. Musicians and artists were also targeted as threats to the success of the revolution. Early on, the Guard focused on destroying old instruments, art, and any form of artistic expression that did not directly support the goals of the Cultural Revolution. Eventually, the Guard decided that the best way to ensure that these art forms remained in the past was to deal with the artists themselves. Painters, instrument makers, musicians, and other members of the fine art community suffered brutal attacks. If not killed, the Guard ensured they would not pass their knowledge and talents to another generation through cruel maiming. Musicians hands were shattered, painters were blinded, and numerous others suffered disabling attacks to forever silence their traditional craft. Eventually, the Red Guard starting setting up public gatherings where "counterrevolutionaries" would be publicly humiliated and tortured. The picture above is one such gathering. The signs around the victims necks were a common practice to perpetuate the Guard's propaganda. These signs would often have messages like "capitalist roadsters" or other brandings denoting opposition the the Cultural Revolution. Tragically, many of the intellectuals persecuted during this time were guilty of nothing more than being talented and well educated.

By this point, the Red Guard had grown so large and gained so much power that it was impossible for anyone to try and stand up to them. Anyone outwardly opposing the Guard was quickly met with imprisonment or death. Nie Yuanzi, one of the adopted founders of the Red Guard, strongly disagreed with the increasing level of violence demonstrated towards the intellectual class and attempted to resign her position in the Guard. She was quickly detained and imprisoned. She ended up remaining in a Chinese prison for almost 18 years before being released in 1986. In one of the darkest moments of the Red Guard's rampage, they instituted the practice of the "Chinese roulette." In this public demonstration, they would line up persecuted individuals in front of a firing squad and randomly execute them. The Guard believed that the individuals not killed were left with a bullet of fear deep inside the brain.

By this point, even Mao himself felt that the Red Guard was out of control. Mao, along with the support of the Communist Party, decided in February of 1967 to form the People's Liberation Army in order to dismantle the Red Guard. Mao and the Party felt that the Red Guard had become a threat to the stability of the revolution and the nation. The PLA spent months trying to suppress and dismantle the many divisions of the Red Guard all around China. However, the Red Guard refused to be disbanded without a fight. The initial non violent approach of the PLA was quickly abandoned when it became clear that the Red Guard would never surrender their beliefs. The violence that ensued made earlier atrocities look mild in comparison. Mass executions of Guard members and brutal confrontations swept all of China. During the PLA's year long campaign, some of the more radical chapters of the Red Guard encountered in southern China were practicing cannibalism as a form of psychological warfare against the persecuted. The brutal conflict between the two armies finally ended on July 27th 1968. Mao called for a meeting with the remaining leaders of the Red Guard and somberly told them that the revolution he had started was over. Although small pockets of the more radical members of the Guard remained, the organization as a whole had finally been disbanded.

In the Sixteen Points document, its is clearly stated that persuasion rather than violence should be utilized in the realization of the Cultural revolution. However, the Red Guard ignored these guidelines. The Guard was more concerned with the absolute success of the Revolution by any means necessary. The persecution of intellectuals began with the Guard shutting down educational institutions and forcing the staff to do manual labor all day in order to give them time to "reflect on their mistakes." In the eyes of the Red Guard, the intellectual class being persecuted was not limited to members of the academic community. Musicians and artists were also targeted as threats to the success of the revolution. Early on, the Guard focused on destroying old instruments, art, and any form of artistic expression that did not directly support the goals of the Cultural Revolution. Eventually, the Guard decided that the best way to ensure that these art forms remained in the past was to deal with the artists themselves. Painters, instrument makers, musicians, and other members of the fine art community suffered brutal attacks. If not killed, the Guard ensured they would not pass their knowledge and talents to another generation through cruel maiming. Musicians hands were shattered, painters were blinded, and numerous others suffered disabling attacks to forever silence their traditional craft. Eventually, the Red Guard starting setting up public gatherings where "counterrevolutionaries" would be publicly humiliated and tortured. The picture above is one such gathering. The signs around the victims necks were a common practice to perpetuate the Guard's propaganda. These signs would often have messages like "capitalist roadsters" or other brandings denoting opposition the the Cultural Revolution. Tragically, many of the intellectuals persecuted during this time were guilty of nothing more than being talented and well educated.

By this point, the Red Guard had grown so large and gained so much power that it was impossible for anyone to try and stand up to them. Anyone outwardly opposing the Guard was quickly met with imprisonment or death. Nie Yuanzi, one of the adopted founders of the Red Guard, strongly disagreed with the increasing level of violence demonstrated towards the intellectual class and attempted to resign her position in the Guard. She was quickly detained and imprisoned. She ended up remaining in a Chinese prison for almost 18 years before being released in 1986. In one of the darkest moments of the Red Guard's rampage, they instituted the practice of the "Chinese roulette." In this public demonstration, they would line up persecuted individuals in front of a firing squad and randomly execute them. The Guard believed that the individuals not killed were left with a bullet of fear deep inside the brain.

By this point, even Mao himself felt that the Red Guard was out of control. Mao, along with the support of the Communist Party, decided in February of 1967 to form the People's Liberation Army in order to dismantle the Red Guard. Mao and the Party felt that the Red Guard had become a threat to the stability of the revolution and the nation. The PLA spent months trying to suppress and dismantle the many divisions of the Red Guard all around China. However, the Red Guard refused to be disbanded without a fight. The initial non violent approach of the PLA was quickly abandoned when it became clear that the Red Guard would never surrender their beliefs. The violence that ensued made earlier atrocities look mild in comparison. Mass executions of Guard members and brutal confrontations swept all of China. During the PLA's year long campaign, some of the more radical chapters of the Red Guard encountered in southern China were practicing cannibalism as a form of psychological warfare against the persecuted. The brutal conflict between the two armies finally ended on July 27th 1968. Mao called for a meeting with the remaining leaders of the Red Guard and somberly told them that the revolution he had started was over. Although small pockets of the more radical members of the Guard remained, the organization as a whole had finally been disbanded.

Aftermath

Although the Cultural Revolution had been officially ended, the damage had already been done. In 14 short months, the majority of China's art, literature, and items of historical significance had been destroyed. The items that remained only survived due to black market dealings and people taking what they could when they fled the country during the revolution. Chinese customs and traditions also took a severe blow due to the death of so many teachers, historians, and religious figures. The Chinese government estimates that around 500,000 people perished during this time period, with another several million people persecuted, imprisoned, or relocated. However, due to the poor record keeping and general chaos of the time, many modern day researchers find these government estimations to be inaccurate. It is more widely believed that the number of Chinese people persecuted during the Cultural revolution was around 40 million, while the death toll is estimated between 1.5 and 3 million.

The extreme hardships and destruction China had endured during this year long revolution was crippling. Although over, the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution took years to overcome. The failure of Mao's revolution sparked many attempted coups from within the Communist Party. The inter governmental turmoil and corruption transferred directly to the people. Lack of funding and resources all but halted the public education system. Also, the huge number of persecuted citizens that had been relocated had no means of returning home. They were also not sure if they would even have a home to return to. Only until the passing of Mao Zedong in September of 1976 did China slowly begin to socially and politically rebuild itself.

There are numerous important people and events not discussed in my summary that were important factors of the Cultural Revolution and the years following it. My summary merely aims to give the most basic idea of the unbelievable turmoil that plagued China during these ten years. However, basic knowledge of this time period sets the stage to understand how the following generation of Chinese people were raised and how they thought. My research findings on the evolution of Chinese music in the 20th century is better understood and appreciated with an understanding of the severe pain and hardship endured by the Chinese people during this time.

The extreme hardships and destruction China had endured during this year long revolution was crippling. Although over, the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution took years to overcome. The failure of Mao's revolution sparked many attempted coups from within the Communist Party. The inter governmental turmoil and corruption transferred directly to the people. Lack of funding and resources all but halted the public education system. Also, the huge number of persecuted citizens that had been relocated had no means of returning home. They were also not sure if they would even have a home to return to. Only until the passing of Mao Zedong in September of 1976 did China slowly begin to socially and politically rebuild itself.

There are numerous important people and events not discussed in my summary that were important factors of the Cultural Revolution and the years following it. My summary merely aims to give the most basic idea of the unbelievable turmoil that plagued China during these ten years. However, basic knowledge of this time period sets the stage to understand how the following generation of Chinese people were raised and how they thought. My research findings on the evolution of Chinese music in the 20th century is better understood and appreciated with an understanding of the severe pain and hardship endured by the Chinese people during this time.

Bibliography

Chesneaux, Jean. China, the People's Republic, 1949-1976. New York: Pantheon, 1979. Print.

Clark, Paul. The Chinese Cultural Revolution: a History. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2008. Print.

Jasper, Becker. Hungry Ghosts: Mao's Secret Famine. New York: Henry Holt and, 1996. Print.

Jones, Andrew F. Yellow Music: Media Culture and Colonial Modernity in the Chinese Jazz Age. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2001. Print.

Karnow, Stanley. Mao and China: inside China's Cultural Revolution. New York, NY: Penguin, 1984. Print.

MacFarquhar, Roderick, and Michael Schoenhals. Mao's Last Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Belknap of Harvard UP, 2008. Print.

Mao, Zedong. Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung. San Francisco, CA: China, 1990. Print.

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. The Communist Manifesto. [England]: Echo Library, 2009. Print.

Meisner, Maurice J. Mao's China and After: a History of the People's Republic. New York, NY: Free, 1999. Print.

Tatlow, Didi Kirsten. "A Grim Chapter in History Kept Closed - NYTimes.com." NY Times Advertisement. 22 July 2010. Web. 17 Aug. 2011. <http://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/23/world/asia/23iht-letter.html>.

Van Der Sprenkel, Berkelbach. "The Red Guards in Perspective." New Society 8 (1966). Print.

Yan, Jiaqi, Gao Gao, and D. W. Y. Kwok. Turbulent Decade: a History of the Cultural Revolution. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i, 1996. Print.