The Blues Tradition

Introduction

Although separated by hundreds of years, the Blues holds many of the same ideas pioneered in ancient Greek music and poetry. There is the use of pastoral writing as well as the idea of a solo performer singing with accompaniment by one instrument. Also, the most important instrument associated with the blues, the guitar, evolved from the cithara.

The Blues is a very daunting topic to try and summarize due to its long and unique history. Depending on which era or geographical location you are discussing, the lyrics and playing style of the Blues can greatly vary. In this section, I aim to only focus on the factors that all Blues musicians had in common during the early 20th century. I will also discuss the Jazz movement that was going on at the same time. While the musical styles are different, the social and cultural issues of the time period pertain to both genres.

The Blues is a very daunting topic to try and summarize due to its long and unique history. Depending on which era or geographical location you are discussing, the lyrics and playing style of the Blues can greatly vary. In this section, I aim to only focus on the factors that all Blues musicians had in common during the early 20th century. I will also discuss the Jazz movement that was going on at the same time. While the musical styles are different, the social and cultural issues of the time period pertain to both genres.

The Blues Musical Form

The Twelve Bar Form

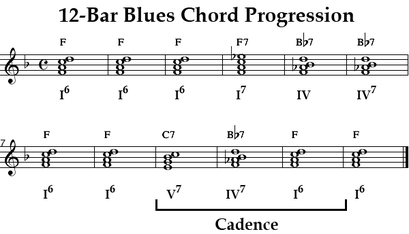

Originating from African American spirituals and chants, the Blues form is a cyclical form that primarily utilizes what is called a twelve bar form. The image to the left is one example of what the twelve bar form looks like notated. While there are many different variations and approaches to the twelve bar form, there are a few factors that are crucial to maintaining the integrity of the form.

First and foremost, the form must have twelve bars that are divided into 3 groups of 4. The time signature is also usually set in 4/4 (four beats per measure). The form begins on the I chord (tonic) and remains there for 4 bars (measures). Then, it changes to the IV chord (subdominant) for two bars and returns to I for two bars. The final section begins on the V chord (dominant) for 1 bar, changes to the IV for one bar, and finishes the last two bars on the I chord. While this is the most basic example of the twelve bar form, it is the cornerstone of most all early Blues music. The variations on this form are literally limitless and present themselves in many interesting and innovative ways. One example of this is present in the image I used to explain the twelve bar form. The image I used shows the addition of 7ths (subtonic) as well as inversions of the root chords. The 7th scale degree, or the leading tone, is used quite often in the Blues due to its unique property of being able to act as a substitute for a V chord. This allows smooth transitions between the three sections of the twelve bar form as well as strengthening the harmonic progression. Another common variation is the use of a V chord on the 12th (last) bar to reinforce the return to the I chord.

The twelve bar form is one of the most well recognized musical forms in popular music. Although pioneered in the Blues genre, it has inserted itself into almost every other genre of popular music. It is even considered to be the basic form used in the birth of rock and roll. To this day, the twelve bar form can be consistently found in some form on the top 100 pop music charts.

First and foremost, the form must have twelve bars that are divided into 3 groups of 4. The time signature is also usually set in 4/4 (four beats per measure). The form begins on the I chord (tonic) and remains there for 4 bars (measures). Then, it changes to the IV chord (subdominant) for two bars and returns to I for two bars. The final section begins on the V chord (dominant) for 1 bar, changes to the IV for one bar, and finishes the last two bars on the I chord. While this is the most basic example of the twelve bar form, it is the cornerstone of most all early Blues music. The variations on this form are literally limitless and present themselves in many interesting and innovative ways. One example of this is present in the image I used to explain the twelve bar form. The image I used shows the addition of 7ths (subtonic) as well as inversions of the root chords. The 7th scale degree, or the leading tone, is used quite often in the Blues due to its unique property of being able to act as a substitute for a V chord. This allows smooth transitions between the three sections of the twelve bar form as well as strengthening the harmonic progression. Another common variation is the use of a V chord on the 12th (last) bar to reinforce the return to the I chord.

The twelve bar form is one of the most well recognized musical forms in popular music. Although pioneered in the Blues genre, it has inserted itself into almost every other genre of popular music. It is even considered to be the basic form used in the birth of rock and roll. To this day, the twelve bar form can be consistently found in some form on the top 100 pop music charts.

The Blues Scale

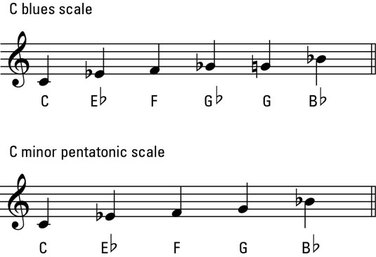

Arguably the most important aspect of the Blues form is the Blues scale. Much like the twelve bar form, the Blues scale is found in numerous different genres and is applicable to a multitude of musical progressions. The scale is based on the pentatonic scale, a scale which omits the use of the 2nd and 6th scale degrees. This leaves a scale that utilizes 5 tones instead of the 7 tones usually used in Western music. The pentatonic scale has a very long and diverse history, but is most often associated with the traditional music of Asia. One of the most interesting attributes of the pentatonic scale is its lack of dissonant intervals. The scale is built so that any combination of scale tones omits the possibility of minor 2nds (also major 7ths, the inversion of a minor 2nd) or tritones. This allows the performer to play any note in the scale at anytime without the possibility of creating a dissonant interval. This was a very important factor in ancient music when musical notation was limited or non-exsistant. It allowed a large number of musicians to play together without fear of creating clashing tones.

The Blues scale is a slight modification of the pentatonic scale. Pictured above, the main difference between the Blues scale and the pentatonic scale is the addition of the flat V (lowered fifth scale degree). Another way of describing the Blues scale is discussing it in relation to the Western major mode scale (C D E F G A B C, in C major). The Blues scale takes this framework and applies the use of flatted 3rd, 5th, and 7th scale degrees. These altered scale degrees have been dubbed "Blues notes" and are the source of the "Blues" sound. The dissonance created by these altered tones adds "flavor" to the melodic line by introducing a note that does not naturally mesh with the chord progression. The altered tones can also be used in combination with the tones present in the chord progression to create secondary dominant chords. Secondary dominant chords are often used to trick the ear into thinking that the tonic (root note) of a piece has shifted to a different tone. Although brief, the use of secondary dominants adds a lot of character to a piece and keeps the listener guessing what is going to happen next.

The Blues scale is a slight modification of the pentatonic scale. Pictured above, the main difference between the Blues scale and the pentatonic scale is the addition of the flat V (lowered fifth scale degree). Another way of describing the Blues scale is discussing it in relation to the Western major mode scale (C D E F G A B C, in C major). The Blues scale takes this framework and applies the use of flatted 3rd, 5th, and 7th scale degrees. These altered scale degrees have been dubbed "Blues notes" and are the source of the "Blues" sound. The dissonance created by these altered tones adds "flavor" to the melodic line by introducing a note that does not naturally mesh with the chord progression. The altered tones can also be used in combination with the tones present in the chord progression to create secondary dominant chords. Secondary dominant chords are often used to trick the ear into thinking that the tonic (root note) of a piece has shifted to a different tone. Although brief, the use of secondary dominants adds a lot of character to a piece and keeps the listener guessing what is going to happen next.

Lyrics of the Blues

Blues lyrics have a very unique relationship to the other aspects of the Blues form. In most musical genres that have a vocal line, the lyrics are sung in a way that creates a melody or melodic line. In the Blues tradition, the lyrics are presented in more of a rhythmic style of talking rather than singing. This is mainly attributed to the form of Blues lyrics. The most common Blues form is an AAB pattern of organization. Applying this pattern to the twelve bar form, the AAB pattern is when the first line of lyrics is sung over the first 4 bars, then repeated over the next 4 bars, and finally a slightly longer line is sung over the last 4 bars. This form was widely adopted due to the very personal nature of the lyrics. The Blues is most often an expression of the deep woes and ailments that affect the Blues man everyday. Often times the Blues singer would sing with so much emotion (or be so drunk) that it was nearly impossible to understand what they were singing about. The repetition of the lyrics allowed the message to be more easily understood and kept the message much more focused.

Perhaps the most important aspect of Blues lyrics is how they set up and compliment the other two aspects of the Blues form. The content of a lyrical line sung before a guitar riff gives that riff an emotional quality. If the lyrical line preceding a riff is very mournful, the guitar riff is then associated with sorrow or wailing. If the line is farcical, then the riff can take on a humorous quality.

An excellent example of all these Blues components can be found in the following video clip. This is a 1967 clip of Son House playing one of his most famous songs, "Death Letter Blues." The song portrays the pain of being left by your woman. The overall intensity Son uses to play the guitar along with the soulful riffs sprinkled throughout shows just how emotionally charged Blues music can be. The lyrics listed beneath the video are the original lyrics to the song Son House wrote. However, as in many live Blues performances, Son deviates quite a bit from the original lyrics around half way through the song. Alternate lyrics are often used by Blues performers to dive deeper into the emotional content of the Blues as well as keep audiences guessing.

Perhaps the most important aspect of Blues lyrics is how they set up and compliment the other two aspects of the Blues form. The content of a lyrical line sung before a guitar riff gives that riff an emotional quality. If the lyrical line preceding a riff is very mournful, the guitar riff is then associated with sorrow or wailing. If the line is farcical, then the riff can take on a humorous quality.

An excellent example of all these Blues components can be found in the following video clip. This is a 1967 clip of Son House playing one of his most famous songs, "Death Letter Blues." The song portrays the pain of being left by your woman. The overall intensity Son uses to play the guitar along with the soulful riffs sprinkled throughout shows just how emotionally charged Blues music can be. The lyrics listed beneath the video are the original lyrics to the song Son House wrote. However, as in many live Blues performances, Son deviates quite a bit from the original lyrics around half way through the song. Alternate lyrics are often used by Blues performers to dive deeper into the emotional content of the Blues as well as keep audiences guessing.

Son House

"Death Letter Blues"

Source

I got a letter this morning, how do you reckon it read?

"Oh, hurry, hurry, gal, you love is dead"

I got a letter this morning, how do you reckon it read?

"Oh, hurry, hurry, gal, you love is dead"

I grabbed my suitcase, I took off, up the road

I got there, she was laying on the cooling board

I grabbed my suitcase, I took on up the road

I got there, she was laying on the cooling board

Well, I walked up close, I looked down in her face

Good old gal, you got to lay here till Judgment Day

I walked up close, and I looked down in her face

Yes, been a good old gal, got to lay here till Judgment Day

Oh, my woman so black, she stays apart of this town

Can't nothin' "go" when the poor girl is around

My black mama stays apart of this town

Oh, can't nothing "go" when the poor girl is around

Oh, some people tell me the worried blues ain't bad (note 1)

It's the worst old feelin' that I ever had

Some people tell me the worried blues ain't bad

Buddy, the worst old feelin', Lord, I ever had

Hmmm, I fold my arms, and I walked away

"That's all right, mama, your trouble will come someday"

I fold my arms, Lord, I walked away

Say, "That's all right, mama, your trouble will come someday"

"Oh, hurry, hurry, gal, you love is dead"

I got a letter this morning, how do you reckon it read?

"Oh, hurry, hurry, gal, you love is dead"

I grabbed my suitcase, I took off, up the road

I got there, she was laying on the cooling board

I grabbed my suitcase, I took on up the road

I got there, she was laying on the cooling board

Well, I walked up close, I looked down in her face

Good old gal, you got to lay here till Judgment Day

I walked up close, and I looked down in her face

Yes, been a good old gal, got to lay here till Judgment Day

Oh, my woman so black, she stays apart of this town

Can't nothin' "go" when the poor girl is around

My black mama stays apart of this town

Oh, can't nothing "go" when the poor girl is around

Oh, some people tell me the worried blues ain't bad (note 1)

It's the worst old feelin' that I ever had

Some people tell me the worried blues ain't bad

Buddy, the worst old feelin', Lord, I ever had

Hmmm, I fold my arms, and I walked away

"That's all right, mama, your trouble will come someday"

I fold my arms, Lord, I walked away

Say, "That's all right, mama, your trouble will come someday"

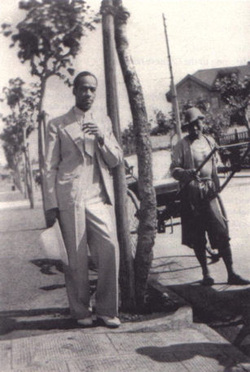

The Blues Man

There are many factors that contribute to the source of a man's "blues." It could be anything from an unfaithful woman to a bad drinking problem. However, especially during the early days of the Blues, racism was one of the main contributors to this feeling of having the "blues." Many of the musicians that I focus on as main contributors to the spread of the Blues in China traveled to China in hopes of escaping the intense racism experienced in America. While each musician has their own specific reason for singing the Blues, one would be hard pressed to find an artist during this time period that was not being oppressed in some way due to racism. However, these musicians turned that bigotry and frustration into an art form that not only served as a form of catharsis, but also spread their tale to a wide audience. This gave other people in similar oppressive situations a way to relate and release along with their brethren.

One of the most controversial aspects of the Blues man is his relationship with the devil. Not all Blues men associated themselves with the devil, but the stigma associated with the Blues at the time was that it was the music of the devil. This stereotype came from stories such as Robert Johnson allegedly selling his soul to the devil at the crossroads in order to be able to play the guitar. There are numerous legends of musicians making deals with the devil in order to gain musical ability or fame from their music. Mostly, these were stories made up after the fact in order to boost the popularity of the artist in question. However, the association was strong enough that there were many churches and groups that condemned the genre as demonic. It even got to the point where the guitar itself was so closely associated with the Blues that it would not even be permitted to enter a church.

One of the most controversial aspects of the Blues man is his relationship with the devil. Not all Blues men associated themselves with the devil, but the stigma associated with the Blues at the time was that it was the music of the devil. This stereotype came from stories such as Robert Johnson allegedly selling his soul to the devil at the crossroads in order to be able to play the guitar. There are numerous legends of musicians making deals with the devil in order to gain musical ability or fame from their music. Mostly, these were stories made up after the fact in order to boost the popularity of the artist in question. However, the association was strong enough that there were many churches and groups that condemned the genre as demonic. It even got to the point where the guitar itself was so closely associated with the Blues that it would not even be permitted to enter a church.

Bibliography

Bolden, Tony. Afro-blue: Improvisations in African American Poetry and Culture. Urbana: University of Illinois, 2004. Print.

Cohn, Lawrence. Nothing but the Blues: the Music and the Musicians. New York: Abbeville, 1993. Print.

Daniels, Douglas Henry. One O'clock Jump: the Unforgettable History of the Oklahoma City Blue Devils. Boston: Beacon, 2007. Print.

Komara, Edward M. Encyclopedia of the Blues. New York: Routledge, 2006. Print.

Palmer, Robert. Deep Blues. New York: Viking, 1981. Print. Evans, David. The NPR Curious Listener's Guide to Blues. New York: Berkley Pub. Group, 2005. Print.

Moore, Allan F. The Cambridge Companion to Blues and Gospel Music. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2002. Print.